INDUSTRIAL CORTLAND

Part I CORTLAND REMINISCES-INDUSTRY-Allan Ardis Posts

These stories about the factories in Cortland were posted in Past and Present Cortlandites Reminisce. Allan C Ardis March 24, 2024

Contents

FACTORIES THE FIRST DAY OF DEER SEASON.. 6

NOTE: A series of stories on the Hammer Room is available on request. AA.. 11

DURKEE’S BAKERY -ELM STREET. 15

DURKEE’S WAS A STOLEN TREASURE.. 15

DURKEE’S THANKSGIVING PUMPKIN PIES. 17

KNOCK- KNOCK: DURKEE’S DONUTS. 18

DURKEE”S AND THE COST OF LOVE.. 19

BROCKWAY’S CHRISTMAS PAY FOR GRANDDAD.. 23

LABOR DAY FOR CONSTRUCTION.. 32

SALUTE TO WAITRESSES, CAB DRIVERS, STORE CLERKS. 37

JUNK YARDS WERE A WORKING MAN’S FRIEND.. 40

INDUSTRIAL CORTLAND

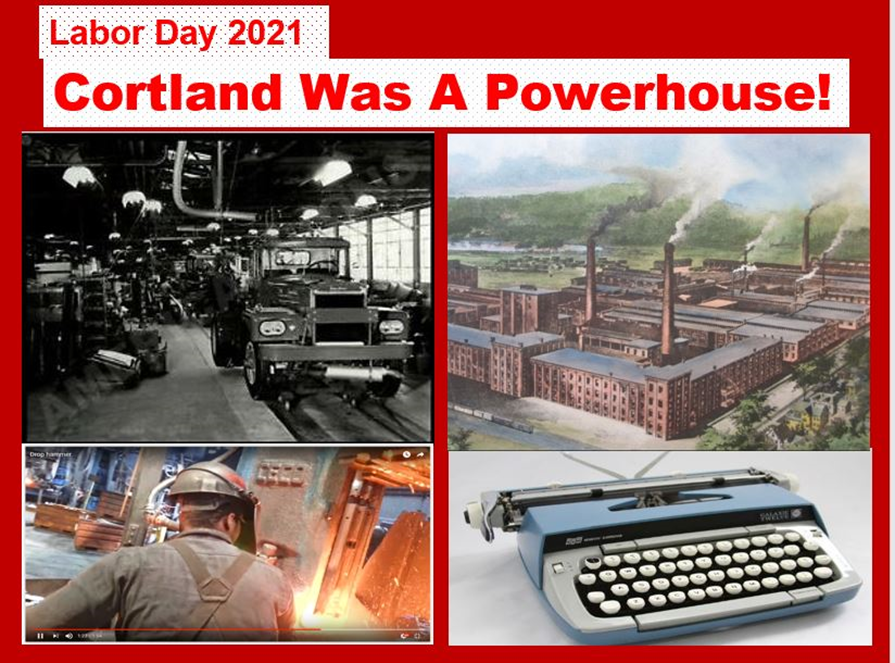

INDUSTRIAL POWERHOUSE

Cortland was an industrial powerhouse. Well trained and motivated workers stamped and bent out metalworks, shoveled coal, harvested ice, strung tennis rackets, varnished boats, assembled typewriters, built machine tools, drew wire, made filters, made fish line, tended dairy farms, pasteurized milk, and, in healthcare, tended to our illnesses, while our civil servants in police and fire made our neighborhoods safe at night. They worked at SCM, Brockway, BTC, Wilson’s, Durkee’s, Champion, Pall Trinity, Edlunds Machine Tools, Monarch Machines, Cortland Line, on scores of dairy farms, and for local gov’t. Pay was good. Workers could afford houses, and VA loans helped build them.. Many were vets of WWII, Korea, Vietnam. Factory and farm work is tiring, but Cortlanders had energy left to make rewarding social lives out of their work, with bowling leagues, birthday celebrations at the coffee break, quick lunches together at diners like T&M, Stevens, Firpo’s, Imperial, and more. We played cards together at lunch breaks. Schools made us ready for this industrial life; all kids, including college bound, took shop classes or home economy. The workweek started with horns at 7:00 AM on Monday morning, and ended with a buzzer at 3:25pm on Friday, payday, and from there to cash the pay check at a grocery store or a beer garden with your comrades. Blue Collar labor made Cortland great.

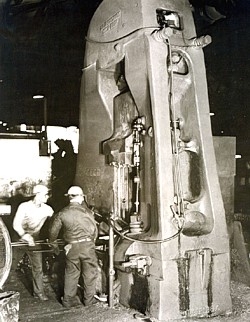

During WWII, Cortland made forgings for tanks and P-51Mustangs on drop hammers like this one at Brewer-Titchener Corp.’s plant on River St. The hard, gritty work was a man’s world. But when every young man was at the front, women ran the hammers, too. At Brockway and Champion Sheet Metal, they made Army trucks, like this one customized for bridge erection, complete with an anti-aircraft gun. Cortland Fish Line made parachute cord. At Smith Corona, in addition to typewriters, shown here is Army green, made rifle parts. Wickwire’s made support hardware. They were all heroes.

Unions were an important element in Cortland life. They gave Cortland a high quality-of-life during its heydays. Major employers including Wickwires wire and cable, Brewer-Titchener forgings, Brockway, Durkee’s, Pall-Trinity filters, Wilson Tennis, and Champion Sheet Metal, were all unionized. Cortland workers won for themselves decent working conditions and wages, health care, and the fun in life such as vacations, bowling leagues, and company picnics. Those Corrtlandites had dignity and pride and a voice in their work. Unions were tough, but so was the management, and we were prosperous.

East side kids early on expected to join a union. Asked for abbreviations in school, our list was UAW, USW, IBEW, ABCU.

Cortland Labor today!

FACTORIES THE FIRST DAY OF DEER SEASON

The start of deer hunting season just about emptied the factories in Cortland. A Tanner-Ibbotson Insurance calendar picture featured this sleeping hunter and it bore a resemblance to Granddad. We hung it in his farmhouse in Virgil for many years. Most of the hunters came back emptied handed, but occasional they got one. The rule on the farm was that if you shoot it, you eat it. Wild game was to be cooked well done, and grandma could always be counted on to do that. Good luck, hunters!

FORGE SHOP

EULOGY TO A HAMMERMAN

The forging plant on River Street is scheduled for demolition. The plant on Part Watson Street has already been razed. Forging was not just a job, it was a destiny. Working at Brewer’s was a tradition. Whole families worked at the plants. Their names were Ardis, Argyle, Arnold, Bordwell, Branagan, Brown, Burnham, Bush, Canillis ,Carmen, Carr, Casidy, Casterline, Caughey, Congdon, Conway, Coon, Costello, Davenport, Dawson, Dehbein, Dillenbeck, Drake, Fox, Funkhouser, Goodale, Greenfield, Gulini, Hall, Hilsinger, Hopkins, Macomber, Marks, Marshall, McCoy, Morris, Murphy, Neville, Nichols, Olmstead, Ostrander, Packard, Randall, Rawson, Rosato, Sorrels, Stevens, Strack, Turner, Warner, Washington, Woods; and more.

Hammers could be heard all over Cortland and even to Homer. Children went to sleep listening to the crashing rhythm as the hammers hit down steadily until midnight. On crystal cold winter nights the booming rank out over the snow even more clearly.

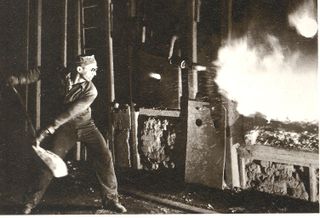

At the Forge Plant, the side walls were totally open, and kids walking along River St. could see their dads inside swinging red hot steel between the furnaces and hammers.

Working conditions were hard, almost brutal. The furnaces roared and spit out flashing tongues of flame across their 5-foot wide openings. Men kept the slots filled with heavy, long bars of steel which heated to a red hot glow at the forging temperature. They pulled hot bars from the furnace all day. Hammermen worked as singles on the “small side” which had hammers up to 2000 lbs. On the “big side”, from 3000 lbs. to 5000 lbs., they worked in crews of up to 4. One man ran the hammer, one swabbed the dies with oil, two swung bars from furnace to hammer to hot trim presses and back. Other men used pitch forks to shovel hot forgings in to bins. Each blow of a hammer made the floor tremor and their spines shake.

Hammers hit down with a “boom’ then shot back up to be released again with a clang-clang mechanical sound. If the operator’s foot stayed on the treadle, there was no more than 2 seconds between blows. Each forging took 9 blows. Helpers had to keep up.

Other men ran upsetter machines and rolling mills. Upsetters operated like a horizontal heavy hammer. The hot bar was grabbed in a giant clamp, and a ram slammed forward to squash its end. The clamp slammed quickly. Fingers were lost. Rolling mills operated like a giant wringer washing machine. The rolls held dies that formed groves as they came together in each fast swirl. The operator had one second to insert a hot bar in the grove. If he missed, the rolling dies would kick him back on his ass, hot bar and all. Not many men had the coordination for the hot roll job.

Hammermen and helper pay was based on time study. To earn top dollar, they worked as a team to make every hammer blow count. The fast tempo was kept up all day. .

Their work was hazardous. One moment of carelessness could cost two fingers. Too often, it did. In later years, they would hold up a hand showing only two fingers as a sign of having worked in the hammer room. Molten steel dripped off a bar in to my father’s boot. Many had their hearing damaged. Some were hit with flying steel parts that vibrated lose and flew about. Despite their individual ruggedness, some men broke down mentally under the pounding and literally had to be wrestled down and pulled out of the hammer rooms before hurting anyone. Disputes were settled roughly; one man put another upside down in a barrel of water; my father knocked the barrel over and saved his life. The insurance company treated their injuries as routine and simply issued a chart listing the compensation for lost eyes and limbs. The accident rate improved when helmets replaced caps and ear muffs replaced wads of cotton in the 1960’s.

They worked through rough conditions. The noise level in the hammer room was 100+ decibels. Communication was an occasional shout under a raised ear muff, followed by a nod. High pressure air blasted past the hammerman on to the dies to blow off steel scale. Sparks, scale, oil, and smoke flew through the air all-day forming gray clouds. Men were blackened from head to toe in the first half hour each day. Despite the roaring furnaces, the temperatures in the winter were as cold inside the hammer room as outside. Men were seared on their front side while icicles formed on the back sides of their clothes.

The hammer rooms were tall, all-steel construction. Originally built with many windows so as to use natural light, the windows had all shattered out decades ago from flying scrap and vibration. On some frigid winter mornings, men would climb up their hammer, douse it with naphtha, then light it to thaw it out.

Even their downtime was rough. They briefly had a hot lunch service, but the Cortland Health Dept shut it down in a thoughtless attempt to improve industrial hygiene. That left working men with a candy bar, cigarette and coffee for lunch. Even the men’s room was crude; it was as black as the inside of a coal mine. It had one dim bulb. The urinal was a length of pipe drizzling water down a wall.

The men endured because the pay was good and the work important. They called the process “hopping bells” as they forged bell-shaped fittings for high voltage power lines. These forgings electrified rural America. Each bell had a hammerman’s initials proudly forged in to it. The construction hooks they forged helped construct skyscrapers, and their forged Otis Elevator bolts held up the elevators in skyscrapers, and still do. They even forged parts for the P-51 Mustang WWII fighter plane.

Despite the heat, the cold, the noise, the smoke, and the hard labor, this work fulfilled a destiny. They were men of steel.

If God was looking for a good hammer crew, He found them in Cortland at the forging plants.

Ka-boom-clang-clang.

NOTE: A series of stories on the Hammer Room is available on request. AA

To hear and see the forging hammers, search YouTube for FIREBALLS-ROCKFORD FORGE https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xmS3LgfdT7E

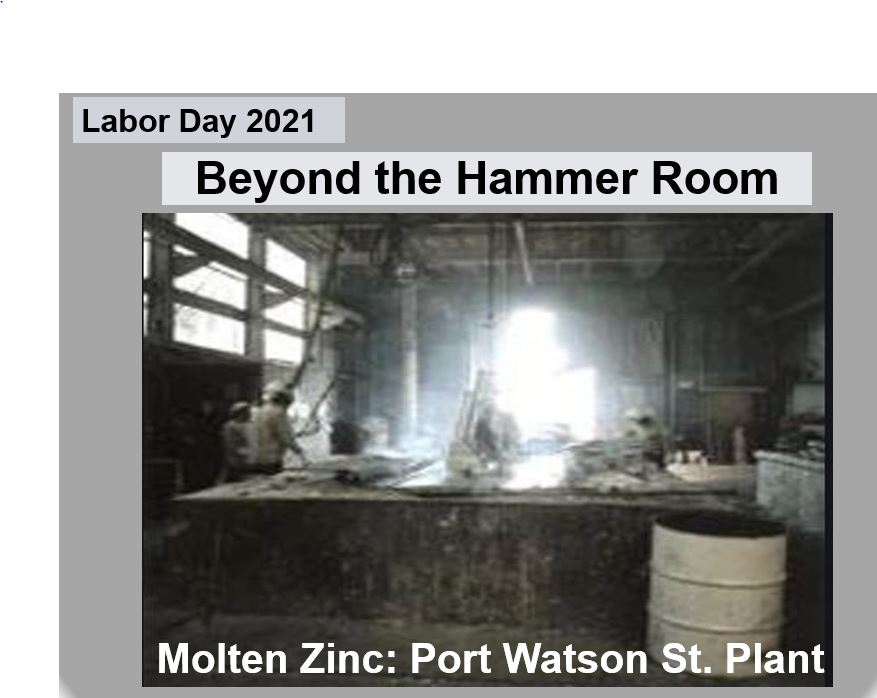

BEYOND THE HAMMER ROOM

The fire and noise of work at Brewer-Titchener Corp up through the ‘70’s is written in the Eulogy to a Hammerman post. The supporting operations deserve just as much respect this Labor Day.

Tool makers machined complex dies from hardened tool steel . Crane operators sitting in open cabs above the unheated the steel storage shed swung 20-ton bundles of steel over to the shears. The shears crunched through bars up to 6” in diameter, and men hand loaded the cut offs on to carts that moved to the hammers. Electro-magnets mounted to the crane swung heaps of steel trim scrap on to trucks headed for Rosen’s scrap yard, and from there by rail back to smelters in Pittsburg and Buffalo. Forged parts were then heat treated, with men loading conveyors that heated then dumped the forging in to oil baths. The oil burned back off in the tempering furnace. We could see mist of black smoke rising as we walked to school. In those days, that was a sign of industry. The initial reaction to environmental restrictions was to only temper oily parts at night to hide the smoke; that was eventually changed. Next, tumbling or blasting removed heavy scale formed by forging. In tumbling, thousands of small forgings were shoveled in to horizontal tumblers that created an intense high-frequency jingle and a cloud of crud that left a taste in the mouth and nose. Masks were of some help. Men desperate for a pay check bid this job. Occasionally the cloud would explode in spontaneous combustion, and the plant Fire Brigade saved the day more than once. Management was happy to give them a dinner for their service.

Machining the forgings with holes, shapes, and threaded fittings came next. Tub loads came in to the Drill Room. Swapping parts in to and out of fixtures all day could be tedious. Time-study set what was called the rate and “making rate’ established the pace and pay. Keeping track of making rate and the hourly bonus earnings somewhat relieved the tedium as the work day went along. One worker one set up two packs of cigarettes on his machine and counted the hours by the pack. The work was a problem for men with arthritis. The steel parts were kept bathed in coolant as they were machined. Constantly having their hands in coolant was tortuous. Even worse was after eight hours of that going out to a frozen car at midnight to go home..

Brewer-Titchener was renowned for its galvanizing operations that coated the parts thickly with zinc. The River St. plant had modest size sulfuric acid tanks for pre-cleaning the parts, then a galvanize tank 3 feet wide and 10’ long. After cleaning, men placed the forgings on handheld racks, lowered them in to the molten zinc, and moved them along to a running water quench. Theirs was the finest galvanize finish in the industry.

However, there was an incident with the acid tanks. Herbie on the Maintenance crew was a bit slow. In this instance, someone took his uniform and soaked it in the sulfuric acid. He wore it the next day until coffee break. When he stood up from the bench, the back of his pants fell off. He was the butt of a bad joke. At least one fellow worker recognized its cruelty. He went directly to the Chief Engineer, Mr. Harrison. Horseplay of any kind is dangerous in a factory and strictly forbidden. Harrison was incensed. He skipped the union process and directly called all the maintenance crew (40) in to line and castigated them all for this incident. The point was made.

The “Carriage Goods” plant on Watson Street plant had six forging hammers and a large sheet metal and welding operation. Unlike the River St. plant, some women worked in the shop operations.

The galvanizing operation at the Port Watson Street plant was a primary component of BTC business. The acid tanks were 3 ft wide and 40 ft. long. The product line at this plant was street light brackets. They were large weldments and clumsy to handle. Overhead cranes move bundles of brackets through the acid tanks and rinse tanks. Used (spent) rinse went down the drain to a pond in the field behind the plant. Cleaned bundles of the brackets moved in to the large and cavernously high galvanizing room. There the zinc kettle was 24 ft long. The lowering of parts in to the zinc was tricky and had to be done by crews of 7 men heaving on ropes and pulleys to lift the bundles up and over in to the molten zinc. If any rinse water remained in the brackets as they went in, they exploded with steam and blasted molten zinc out an end. Clouds of zinc fume billowed up the stack every day, out to the wind, and across Cortland. No one in Cortland needed to buy zinc supplements at the vitamin store, they just didn’t know it. (Author’s note: as children we lived just across the street from the galvanize operation.)

BUY AMERICAN

Brewer Titchener Corp with the forge shops and hammer rooms and galvanizing was one of the most progressive company in Cortland. They had a union, but never an authorized strike. They promoted from within and paid for employee education. At a time when America was opening its trade to other countries, their production manager, Rocky Roe, declared that Brewer-Titchener will buy only United States Steel for its plants.

Salute to Brewer-Titchener Corp. this Labor Day

DURKEE’S BAKERY -ELM STREET

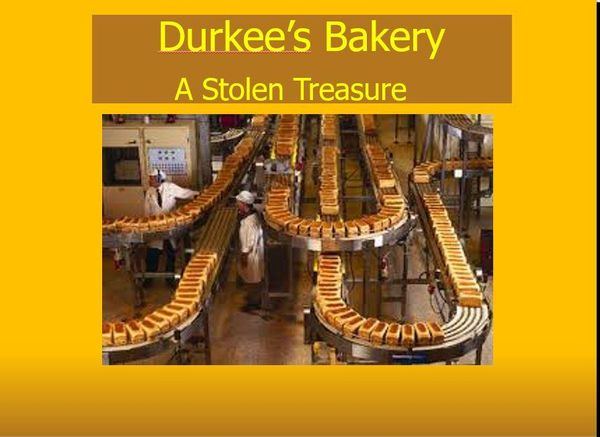

DURKEE’S WAS A STOLEN TREASURE

The Durkee’s Bakery building on Elm St in Cortland was a handsome, pristine white facility on the outside and inside. The floors were polished hardwood spotlessly cleaned every night. Sunlight flooded in at dawn from windows overhead. The delicious aroma of warm bread and fresh oven pastries permeated the neighborhood. 250 workers had good paying, unionized jobs. On the bread making side, hands never touched the bread. Flour came in by tanker rail cars. It was piped in to giant mixers and whipped in to dough that was poured in to long wagons. Mechanical arms snatched dough and slapped it into loaf pans. The pans ran along on a ceiling suspended conveyor above the ovens. The warmth raised the floured dough and made it ready for the bakers to push in to the ovens. As they came out, the loaves moved on into oscillating knives that sliced the loaves and blew them in to bags, then conveyed down and across the basement area to shipping.

On the Pastry side, Durkee’s was more labor intensive, for example, in making cinnamon rolls, dough was stretched on to a conveyor, flattened, squirted with cinnamon, rolled in to a continuous roll, and chopped. Girls grabbed the doughie globs and plopped them in to baking trays and loaded the trays on to racks. This conveyor sped along at a rate of a thousand buns per hour. If any dough fell off the end of the belt, the superintendent, a German, would yell at the girls in German mach-schnell! Faster!. Remember the I Love Lucy episode where Lucy worked on a pastry conveyor? It was like that. Each day at Durkee’s started at 1:00 AM with mixing breads, cookies, pies, and doughnuts. It ended at midnight when tractor trailers loaded with bread and pastries from Cortland went out for distribution across all upstate NY. The work was hard and relentless, often with 10 or 11 hour days for women and 12 to 14 for men. However, the atmosphere was friendly. The bread workers were mostly men; the pastry workers mostly female, so romance was always in the air. There were more union grievances filed over lovers’ quarrels than over disputes with management. The problem was that many of the lovers were married, just not to each other!

Durkee’s was a fine company and closed only because of financial manipulation. Out of towners came in, seemed to buy the bakery, but only collected the receivables and stiffed the employees on two weeks pay. The Durkee family and Marine Midland tried to saved the business but could not. Would be nice to bring back the work and the aroma for Labor Day 2021

DURKEE’S THANKSGIVING PUMPKIN PIES

November in Cortland was cold and gloomy, but brightening everyone’s spirits was the start of the holiday season with Thanksgiving dinner and pumpkin pie. Durkee’s Bakery on Elm St. was a big unionized operation that distributed bread and pastry throughout NY state. Their seasonal specialty was pumpkin pie. To get started, their pastry department rolled out the pie-making machine. Pastry workers stood around this carousel machine as it revolved and one-by-one placed down the pan, laid the dough, plopped in a scoop of fill, sprinkled seasoning, checked weight, racked the pies, and pushed the racks to the ovens. Pie making was boring but workers chatted about home and holiday preparations as the pies moved around. At the ovens, pies were baked 12 across on automated shelves. The aroma of fresh pie was mouth-watering. All of east-end Cortland smelled of baking pumpkin pie. The results were wonderful, but there was a problem. In the course of a workday in the bakery, employees occasionally snatched a donut or cream stick to eat. Pilferage and eating on the job was not condoned, but not much punished either. Except when it came to the pumpkin pies. Many pies disappeared out the shipping dock door and in to employee cars. My mother, who worked in the Pastry Dept, said it was an unnegotiated employee benefit. It was not. Customer orders could not be fulfilled. Durkee managers posted themselves at the dock door to guard the pies until the trucks pulled out. Their diligence stopped this “fringe benefit”. All was okay, though, because as good as a Durkee pumpkin pie was, Grandma’s homemade pumpkin pie was even better!

KNOCK- KNOCK: DURKEE’S DONUTS

The hammering, sawing, and punch press sounds of industry in Cortland were comforting reminders of prosperity. However, the knock knock of Durkee’s bakery donut production was not. It was loud. It interrupted my sleep and that of many other east-enders. The bakery’s daily pastry making began at 1:00 a.m. and cycled through the day with buns, cookies, cakes, and pies, until the donut line started in late evening. From vats of dough mix, donut circles were extruded in to the fryolator, and continuous lines of donuts flipped on to cooling conveyers. Further along, factory girls and boys scrambled and hand packed every last donut, working late in to the night. Along the way, sugared donuts were diverted in to the sugar coating tunnel. The tunnel was a long, steel spiral wound barrel. As it revolved powdered sugar was injected in it and donuts were sugar coated as they tumbled through. The powdered sugar tended to cake on to the inside of the tunnel. A steel hammer banged hard on the tunnel every revolution to loosen it. It could be heard for over an hour each summer evening blocks away coming through the open windows of the skylights and in to apartment bedrooms. Thank you, Durkee’s for the job, but don’t blame us for being sleepy when we come in at 1 a.m.

DURKEE”S AND THE COST OF LOVE

Many factory workers around town worked a second job, usually to pay alimony and child support, at Durkee’s Bakery on Elm St.. Throughout the day, bread and pastry baked goods came down the conveyors to a large staging area at the sublevel. They were boxed and stacked in to loading preload spots. The loading crews came in at 4:00 pm and started loading the baked goods into distribution vans and tractor trailers. Loading went ton to 10:00 pm or midnight. Each stack was wheeled up in to a tractor trailer by muscle power. The loaders had already worked all day, and now they worked half the night loading trucks. One night, a truck driver claimed that his trailer was short some boxes of bread,. The Shipping Supervisor, Marv, suspected a ruse, so he ordered that the entire eighteen-wheeler be unloaded, recounted, and reloaded. It would take another two hours. No one moaned, they just did their job. How these men could work until 2 a.m. then go pound steel all day was amazing. Their cost of love was high.

DURKEE COMMENTS

Allan: At age 17 I worked one summer in the shipping department. Durkee’s required long hours mid-week to meet the cycle of grocery sales, especially in the summer. One workday I sat outside on the steps exhausted. Mrs. Jane Durkee came by and inquired if I was okay. She was very kind. Thank you, Durkee family. A year later, I was a college drop-out and back at Durkee’s on Elm St. with a full-time job as a dough-stretcher on the cinnamon bun making line. I asked the superintendent how to get ahead in this job. He said do back to college. .

Comment: Speaking of Christmas Parties, I can’t help but laugh remembering my parents saying that one of our neighbors was so drunk at the Durkee’s Christmas Party that he lost his false teeth down the toilet.

Reply : Bill Forney worked in the Bread shop. Wendy Forney was the foreman in the Pastry shop. I knew Wendy. He was a fun guy. However, foremen were in the union, and he was very embarrassed at one union meeting when my mother turned him in for cheating her out of a dime per hour for several months. When pay was $1/hour, a dime was a lot. He just didn’t want to do the paperwork to give her an extra due for working the front belt job. The Union business agent made Wendy an example management tyrants cheating poor working women. Poor Wendy that day; he was more a lover than a tyrant.

COBAKO BECAME DURKEE’S

Cobakco was Cortland’s first large scale bread bakery. It was located on Huntington St. Durkee bought them, and moved the operation and employees over in to a very modern, automated, efficient operation on Elm St. That Elm St. building now sits dilapidated, but at the time it was handsome and spotless. In early 1972, supposedly “midwestern businessmen” bought Durkee’s. Within weeks, it was closed down, with no warning to anyone. They collected the Accounts Receivable, did not pay the Accts Payable or the employees. Their paychecks bounced, but Marine Midland Banks honored the checks anyway. It was all in the newspaper, and I lived next door on Durkee property. In those days, all that manipulation was highly criminal.

BROCKWAY MOTOR TRUCKS

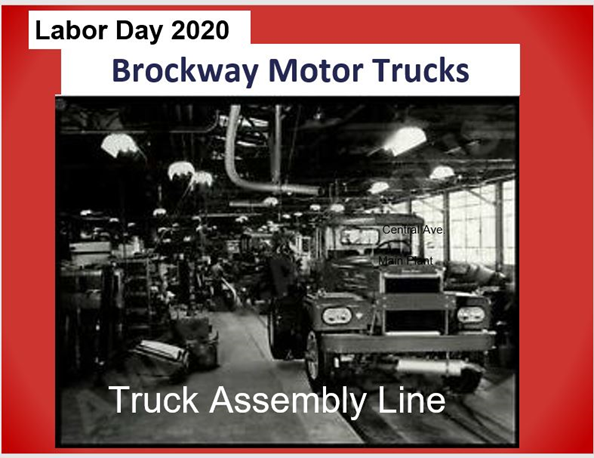

Brockway workers assembled the finest heavy-duty trucks in the industry. They were paid well and worked hard. OverDrive magazine praised their craftsmanship. The praise was shared with their co-workers at Champion Sheet Metal where they produced the handsome Huskie cabs.

Brockway in the 1950’s-60’s was a pleasant workplace. The assembly line moved along at a pace that allowed men to smoke pipes as they ratcheted down parts. The trucks were pulled along manually using block-and-tackle. The building was open to the sidewalks on four sides. Kids walking up Elm St. to school could say “hi” through open windows to upholstery shop workers inside. On Central Ave. coming back, kids walked past large openings and said hi to granddad in the boiler room. Before 1950, men on the “bull gang” kept the factory warm by shoveling coal into a boiler. When it was replaced by gas-fired boiler, safety laws required having one man left as a tender. The tender was paid triple-time for working on Christmas, so the family got granddad to Brockway for the holiday no matter how great the blizzard. The union came in in the early 1950’s. Management relations stayed amicable. The company was getting out seven trucks per day, and that was fine.

As the country prospered in the 1960’s, production and the demand for labor went up throughout industry in Cortland. Employers competed for workers. Brockway attracted many of the best mechanics in Cortland by offering top pay and lots of bravado. Brockway Huskie emblem stickers and buttons and coins were everywhere. WKRT radio hyped working at Brockway. Pictures of the Brockway general manager as a Boy Scout appeared in full page ads in the Cortland Standard. It all worked.

The pace at Brockway picked up after 1973 when the master assembly-line chain was installed. This chain stretched the full length of the plant. Its powerful motor set the pace for all 500 workers from 7:00 AM to 3:30PM.

The assembly line started at the Pendleton Street overhead door. Steel channels were laid to form the chassis, then riveted together and connected to the chain. As the chassis moved along, brackets, axles, engines, transmissions, and cabs were fed in from subassembly lines. Every workstation was timed to keep every worker hopping and bolting on parts. Engines came from Detroit Diesel, Caterpillar, or Cummins. Mack engines and parts were not used. Sales had said if you want a Mack, go buy a Mack. The truck chassis passed through painting and baking, then on to final trim out. The last station was oil and fuel. Sixteen hours after the truck started down the line, a driver slipped behind the wheel, turned a key, and with a roar a new Brockway rolled. A loud warning buzzer sounded as each truck drove out on to Hubbard Street. Brockway boasted to customers that they tested each truck on the rolling hillsides of Cortland County. Insurers made them stop that.

Brockway work life had industrial charm. On cold winter mornings, when coffee was ready for alternating parts of the line, across the PA speaker bellowed, “iron’s in the fire”, meaning come and get it. In the company canteen, worker comradery was poured on with the coffee.

Brockway was a safe workplace with few hazards. But, they had one of Cortland’s rare industrial deaths. A warehouseman horse-playing with a high-lift fork-truck tipped it over on himself and died.

Brockway’s annual picnics and clam bakes were a blast. Every heavy trucking company on the East Coast was invited in. Everyone admired the Goodyear blimp, but only customers got to ride in it.

The union relationship was workable. The union was tough and brought in good pay and decent working conditions. But management was equally tough. For every penny of pay added, productivity was increased. Work-rules were strictly enforced. There was no time allowed for an idle word. Brockway line management was as equally unified as that of the union.. Ninety per cent (90%) of the cost of a Brockway was in the purchased parts, not the local labor. Carefully selected, highly productive, trained, motivated workers made Cortland workers affordable.

This Labor Day 2021 we remember the pride.

BROCKWAY’S CHRISTMAS PAY FOR GRANDDAD

Up until the 1950’s the Brockway Truck plant between Elm and Clinton was heated by coal fired furnaces stoked by the “bull gang”. Natural gas replaced coal when the gas pipeline came through Cortland. Brockway was then heated by gas-fired high-pressure steam. The boilers be checked every day. Holiday pay was triple-time wages. The boiler man went to the bull gang man with the most seniority, my grandfather, Clint Congdon. He lived five miles out in Virgil on hilly Pge Green Road. Despite the heavy snows at that time of year, he plowed through every blizzard to get to Brockway on Christmas Day and earn triple-pay per hour. There was always a clamor in the farm house to get him bundled up, in the car, and launched up slippery roads to get to town and over to the Brockway factory. The family would have used a team of sled dogs if necessary to get him there. His unfaltering determination to get there was equal parts dedication to the job, breadwinner for the family, and an opportunity to drink a beer while there. He got back safely. Merry Christmas.

COFFEE BREAK TIME

Coffee break venues varied. At the Brewer Titchener forging shops, a coffee wagon rolled around the hammer rooms and hammer crews alternated getting coffee while the kaboom-kaboom of other crews continued in the background. Later a lunch room was carved out, but coffee on the wagon was let them get back to the furnaces quicker. Durkees Bakery on Elm St had a coffee room, and workers had to punch out for their break and run to the break room then back. Or, they could slip on a jacket and just step outside for a cigarette, then punch back in. Brockway had a workers coffee room. One of their supervisors would put out a message on the PA system that the “irons in the fire” to signal coffee was ready. That PA announcement was warm and comforting on a cold winter morning in Cortland. Work never stopped. Relief crews moved up the assembly line leting workers go for coffee. A construction sites, workers had coffee trucks roll up outside the project. They stood in the snow or sat on lumber to enjoy a coffee and a cigarette and some chat. Garbage haulers and other outside workers timed their break to be able to swing by Firpo’s, where Firp would have the hot cup waiting when you stepped in. Many enduring friendships, and even some marriages, were started on coffee breaks in those days.

COOPER FOUNDRY

Cooper’s Foundry, built on the banks of the Tioughnioga River, was near the bend in River Street. the foundry was one of Cortland’s oldest factory. The shop took in raw copper and iron and melted and cast these in to into machine parts. In the days of great mechanical machines, that was a good business. Back in the 1950’s, there was still an island separating the East and West Rivers before they merged into the Tioughmioga. Coopers Foundry had built a dam with an electrical generator across the West branch river to a small island. The dam was narrow at the top, bu with boyhood daring-do we walked across the dam to fish on the oher side. Older boys crossed over with their girl friends for romantic privacy. Cooper’s generator fed electrical power to the nearby Brewer-Titchener Corp. forge shop. One of the old-time engineers at BTC told how when the river was low, the power went down, so did the lights at the forge shop!

FACTORY LAYOFFS

Back in the days of factories, Cortland workers experienced jobs layoff on a regular basis. The ebb-and-flow of business cycles caused periodic unemployment. No one had more than a week’s pay in their pocket. They got through with the help of unemployment checks, the govt surplus food program (now called SNAP), borrowing from relatives, eating more out our garden or that of our neighbor, and feeling under the cushions for loose change. They got through until the next boom started. The diversity of industry in Cortland- from trucks to typewriters, tennis rackets, fish line, steel wire, forgings, tennis rackets, boats, dairies, and regional bakeries- helped because when one business was down, another might be up. Today it is service workers in hospitality that are effected most. The infrastructure is still there to get people through an economic crises.,

Comment on Hiring and Layoff

The unemployment crisis that we are now facing was a common occurrence in the 1950s and onward during the prosperous industrial days of Cortland. Layoffs occurred regularly as business cycles or the seasons changed. For example, typewriters were often a Christmas gift, so SCM hiring went up in the Spring. Kids ate more sandwiches at home in the summer, so Durkee’s Bakery employment and hours went up in during that school season. Being caught in a lay-off was always difficult, but unemployment insurance smoothed over the change. The NYS system worked smoothly. Unfortunately, that was not the case for some Cortland workers who followed the factories when they went South. Most southern states make it difficult collect unemployment insurance. Don’t be surprised if when Cortland workers migrate back home.

SMITH CORONA MARCHANT

Labor Day Tribute to the workers at Smith Corona Marchant. SCM workers made Cortland the typewriter capital of the world. At its peak 4,000 worked at multiple plants in Cortland county, working round the clock in three shifts. The original typewriter had moving metal arms for each letter. Each stroke was powered by a finger tip, This brilliant design required precision manufacturing. Model Room workers and Tooling Machinists were graduates of a 4-year apprenticeships sponsored by SCM. Production on the shop floor required hundreds of workers, mostly women, to operate punch presses to stamp out parts. Their hands and arms were strapped to the press with leather harnesses. Each time their foot triggered the treadle, the die rammed down and their arms were jerked back by the harnesses. Nonetheless, fingers were sometimes crushed. Operators learned the rhythm of the machine and too avoided getting jerked. All work was time-studied and paid on piece-work. The pace was rapid, and the building was filled with the clatter of dozens of punch presses running all day and all night. Never a second was lost. Operators lifted parts from bins, and stock-boys kept the bins filled. Operators dealt with the monotony by mentally “zoning-out” all day while keeping an alert eye on the movement of the dies. Daydreaming could mean getting fingers crunched. Everyone was covered with light oil. Parts were manufactured on Huntington St and later in the new Cortlandville plant. Cortlandville was modern, but windowless. It was sweltering hot in the summer. Workers struggled among themselves to keep industrial fans aimed at their workstation. The assembly work was done on McLean Rd and in Groton.

Repeated attempts at unionization were unsuccessful, a testimony to a progressive minded management that provided decent working conditions and respect for employees. Pay was good, breaks were reasonable, the cafeteria was wholesome. Camaraderie was strong and fostered by the bowling league and employee events. Men and women worked together, so of course there was some romance.

Management had just two big screwups. Almost all the Cortland factories in those days took annual vacation in July. Several including Brochway and the forgeshop were all men . SCM with mostly women workers switched their vacation shutdowns to August starting in the 1960. The change broke up family vacation fun time together. There was no apparent reason for the change. In 1968, SCM built a new plant in Orangeburg, SC, to take advantage of cheaper labor. Two yers later, it was closed and the work returned to Cortland. Newly industrialized agricultural workers in the south did not have the industrial skills to compete with the productivity level of Cortland workers who had six decades typewriter manufacturing experience and skills.

TRUCKERS AND TEAMSTERS

Truckers based in Cortland kept the economy rolling. Flat-bed truckers moved materials between local factories and warehouses for all the businesses in town. Small tankers kept the milk flowing to the dairies and food processors. Box trucks kept businesses and schools stocked. Long-haul truckers brought in steel, lumber, and raw materials and hauled back out typewriters, boats, tennis rackets, fish line, baked goods, filters, and farm produce. Farm and factory depended on them. Cortland’s products were distributed across the state and country. Trailers were loaded all day while drivers paced patiently and watched the weather. No matter the snow or sleet, they were going out. When the load was ready, they got behind the wheel, pulled out on the streets and roads. We heard the gunning of engines and shifting gears as they got up to speed..

Driving was hard work. They had to be alert constantly. Danger was at every icy stop light and snow-blind corner and around every hair-pin curve in Rte. 11 coming up from Binghamton. Driving on I-81 was a little better, but its danger was iced over pavement and cars that put trucks in to in to jack-knife positions. Hours were long and too often exceeded the legal limit until they were pulled over by the Smokies and fined. Trucker food gave them gout.

But being a trucker had its benefits. They were independent. No boss was breathing down their neck. Pay was good. They had the respect of car drivers that shared the road. They had a special camaraderie with their fellow truckers that jabbered with them on C-B talk all day and night. More than once they sacrificed themselves to save others and earned their title Knights of the Road.

“10-4, rubber duckie” this Labor Day 2021 for Cortland truckers.

COAL STORY

Coal kept Cortland houses, factories, and businesses warm this time of year. Bull-gangs of men shoveled coal in to furnaces at Brockway, Brewer-Titchener, schools, hospitals, and more. Coal rolled in to Cortland in railroad coal cars. Some unloaded at the factories. Rail cars with consumer coal backed-up on along earthen ramps running up to coal barns. At the top, they dumped their loads in to the bins with great noise and dust clouds. Trucks delivered coal to all the houses in Cortland. Most, like my grandparents’ farm house, had coal chutes and a coal bin in the basement. Last chore of day was to send an uncle down to stoke the furnace and get heat drifting up the open registers all night. Coal ash was collected by the city and sprinkled along the streets and roads. Ash is more environmentally friendly than salt. Trucks laden with coal ash gunned their engines and rolled through the pre-dawn darkness to get the roads ready for workers. Kids awoke hearing clink- clink – clink of coal truck chains in the snow. It still echoes in my mind.

COAL Comment; I’m glad you asked. Excelsior Street and Garfield run parallel, and in our childhood there were RR tracks running parallel between them. On the Excelsior side of the tracks, there was a giant coal bin sat at the top of an earthen railroad ramp. Rail road coal cars were backed up this ramp in and in to bin, also called a coal barn. The coal dropped from the car in to wooden hoppers. Local trucks loaded from below the hoppers, then pulled out the yard driveway on to Elm St. This coal business had an office at the corner of Elm and Excelsior, facing Elm. The business was named A.T.Dunn and had a large chunk of coal mounted on a pedestal out front. Some bully once threw my friend David Lane’s winter cap on to the office roof. Together we trudged through the snow carrying a ladder up from River St. to get the hat back down. Do you remember this coal barn? Are the tracks still there?

LABOR DAY FOR CONSTRUCTION

Construction workers made Cortland prosperous in the 1960-70’s with highways, college bldgs. and factory expansions at SUNY, SCM, BTC, ChrisCraft, and Brockway. These workers were heavy equipment operators, signal men, rod busters, cement screeders, steel workers, shovelers. pipefitters, plumbers, electricians, and more. From April to November, they made long commutes and worked long days. The peak of construction was the interstate highway project from 1960-1970. Hillsides were moved and rivers dredged as roads and bridges went in. Cortland factories stayed busy fabricating materials for the projects. Brewer Titchener provided light poles and heavy electrical hardware, Champion Sheet fabricated guard rails, and Wickwire strung cable and wire for the road. Stone quarries in Homer dug up and crushed bedrock for road bases.. Concrete plants on the outskirts of Cortland ground out cement. That kept Cortland awake 24 hrs. per day with the noise of grinding rock. It created clouds of dust. Food service trucks from local diners showed up for coffee break and lunch time with donuts and sandwiches to keep hard workers fed. The work was hazardous. Many were injured. My brother fell through a roof and hit a concrete floor 24 feet below. Workers Comp paid, but not enough.

The wages were good. They paid taxes and contributed to Unemployment Insurance in the summer months, then drew unemployment in the Winter. It was just enough to squeak by on, but many supplemented their income. Some played guitars on weekends.. Others plowed driveways and drove winter bulldozers for the construction companies plowing factory parking lots.

Construction work was proud work. They knew that sidewalk superintendents driving by were watching them in awe as they moved earth and swung steel girders. They made Cortland ready for prosperity. We pay tribute to construction workers this Labor Day 2021.

One such day, Tony from a construction headquarters came by our maintenance department and asked us to throw them some work. He told this story: business had been good, they decided to expand. They won a million-dollar job in the NJ/NY metro area. After they parked their construction trailer on the site, another trailer pulled up alongside. Two big foreboding men came out and over to say that they were from the union, and they were going to help pick workers for this project. They did, and within weeks the project became a disaster. Tony’s company announced that we were pulling out. The mean-looking men came back and said, No, you’re not leaving, “We like you. Understand?” They did, and stayed to the entire project end, losing big money. The lesson they learned was don’t leave Cortland!.

LABOR DAY FARM LIFE

BRINGING IN THE HAY!

Everyone worked on the dairy farms to bring in the hay at this time of year. Farmers drove the tractor pulling the baler, and young men pulled up the bales while earning money for school and getting tanned. Topped-up full hay wagons were switched for another. The hay arrived at the barn and bales were thrown on elevators that took them in to the loft. As kids, we were sometimes allowed to ride the hay wagon and climb into the loft. As late day came and the farm air cooled, we accompanied the farmhands in to the pastures to bring the cows back to the barn for milking. Everyone of all ages helped on the farm. Trekking across the rolling Virgil hillsides alongside the cows worked up a good appetite. We left milking to the farm hands and ran home for dinner. Summertime meant plenty of fresh corn on the cob, yellow and string beans cooked in milk, fresh potatoes, and carrots, finished off with strawberry short cake. No rich man every ate better! Summer nights meant cool evenings and open windows. We were serenaded to sleep by chirping crickets and cooing owls. We slept peacefully because Granddad had sprayed the room with puffs of bug killer. It worked well and probably was not good for us, but, hey, I’m still here and telling you about it. Good night.

TRIBUTE TO FARMING

Everyone on a dairy farm worked and contributed to the vitality of the Cortland economy.

Farmers were men and women of dedication and fortitude. Farm work is hard now. It was even harder sixty years ago. Chores started before dawn. They fed and milked the cows, lugged cans of milk to the cooler, loaded the milk truck when it made its daily stop, cleaned the barn, and then milked the cows again that evening. In the Spring, the day was spent preparing the fields. In the Summer, they took in the hay and thrashed the oats. In the Fall, they chopped corn and filled the silos. In Winter, they had the added chore of plowing snow so that the milk truck could gun its way to the barn for its daily pickup. Farmers went out in snow, rain, sleet, and bitter cold. Weather was no obstacle.

Farm work had the same hazards, accidents, and monotony as factory work. They, too, had exposure to chemical toxicity for which no one at the time understood the effects. They adjusted themselves to the solitude of sitting on a tractor seat all day. There was no coffee wagon with coworkers to chat with at break time, though they might pop in to a warm kitchen for a cup.

Milk went to a dairy. The dairies were sometimes capricious. They might reject good milk when they had an excess. A farmer then had to watch his daily labor be poured out. He held his tears.

Farm life was a good life. The farmer was his own boss. He found companionship at the Grange, or in town for lunch at Firpo’s, or at the feed store next door. The farm had a stream of service providers that came by often to advise on farm activity and to share some local humor while there. The farmer’s achievements as with prize cows or vegetables were celebrated at the Cortland County Fair each year.

Farmhands were treated as part of the family. Some were young men needing an income while still in school. Others were family men with their own homes that needed a steady job. Above all else, farm work was steady.

Everyday farm activity had unspoken rewards. These memories include: trekking the hillside pastures on a summer afternoon to bring the cows; watching the hills turn from green to golden to white and back again; walking through aromatic oats in the loft; riding the wagon out to load hay or later to gather apples to make cider; trudging through Spring slush to gather maple sap and then boil it down to syrup and maple sugar. Farmers ate like kings when the potatoes and corn and pumpkins were ripe for picking.

Occasionally there was a bonus at the barn when on a cold night a cow gave new life. It was never easy for the cow or the farmer..

Most rewarding of all was the closeness of farm families. Farm life required cooperation and sharing, and in it they found love, harmony, and kinship.

We salute the farmers of Cortland County this Labor Day 2021.

THE SERVICE INDUSTRY

SALUTE TO WAITRESSES, CAB DRIVERS, STORE CLERKS

This Labor Day we salute the women and men in service jobs throughout Cortland. Even years ago, Cortland had scores of restaurants and diners employing hundreds of waitresses and servers. Most had regular customers who were greeted with smiles and sometimes a waiting cup of coffee. Waitresses were on their feet all day and wore out their shoes hustling water, coffee, food, and dishes. They depended on tips. Some customers were generous to show their appreciation for good service. It was all cash. The only benefit was the warm feelings from working with people all day, not machines. Most had to have a factory job, too, to get insurance. More than once I saw a waitress with a golden heart be generous with her tips and time when a working man just needed a dollar, or another waitress just needed a friend.

Salute, too, to other Cortland service workers. Store clerks stood on their feet all day running manual cash registers in the new “supermarkets” like A&P and Acme that came to Cortland in the 1950s. We depended on the clerk for accurate punching of all those keys. At gas station, attendants went out in subzero weather to pump gas and check the oil. In motels, housekeepers quietly changed bed sheets, a most tedious and laborious task. Garbage truck crews hung on the side of their truck and with smiles on their faces snatched our cans. And there were more service workers that we recognize this Labor Day 2022.

HEART OF GOLD

I was in the Dunkin Donut shop one night in the ‘70’s when a fellow came and got a donut and coffee and paid for it and a tip with a bag of 1,600 pennies. The waitress had to count them all out. The fellow was no doubt a lonely young man and making the waitress tediously count out the pennies in front of him was the only way he could get the attention of a pretty girl on a Friday night. Sadly, Cortland was full of such cases. Good thing that Cortland also had waitresses with a heart of gold. She was patient, counted it all out, and gave him a smile. She had a heart of gold.

AFTER THE PROSPERITY

CLEANING UP CORTLAND

Life during the factory era was good. Everyone had a steady job and security. No one worried at all about the pollution caused by smoke and effluent from the factories or from the smoldering dumps, car junk yards, and sewage resulting from the discards of an affluent population. Smokey industrial plants and smoldering dumps were everywhere. The new Cortland high school was built over the biggest dump in town. Cortland and Homer had several car junk yard ugly sights and leaking oil. Cortland treated household sewage before it went in the river, but Homer did not. All the factories spewed smoke and fumes. Gasoline stations had leaky underground tank leaks. Etc.

Then began the cleanup in the early 1970’s.

Rosen’s Scrap yard on Port Watson St. became pilloried years later as a polluter, but for decades it was simply a part of the metalworking process, which was done by many factories throughout Cortland. Most of it was steel, which he sent by rail car back to steel mills in Buffalo and Pittsburg where it went in to the next batch of steel production (steel making starts with about 35% scrap, the rest is ore). While Rosen processed mostly industrial scrap, the other junk yards reclaimed automobiles. Autos had oil, fluids, battery acids, and gasoline in them which leaked out in to the soil.

When the EPA came along in 1971, my first job as a young engineer at Brewer-Titchener included making out reports to the state as to how covered the river was with oil from out factory outlet. Nobody yet cared. However, by 1976 that all changed and great alarm went off if even a wisp of oil was seen. Before that, in the 1950’s, as boys living on River St., we kids went down to river to watch federal contractors plow dumps in to the river, We watched cans, bottles, trash, and even a dead cow float by. Homer did not even treat its raw sewage at that time. I am not absolving Rosen’s yard from having polluted, but saying that he was just part of a process that everybody accepted as normal at that time.

JUNK YARDS WERE A WORKING MAN’S FRIEND

Junk yards are not handsome, but they are part of the industrial and cultural history. Until about 1980, backyard mechanics went to Finkelstein’s on Port Watson St get spare parts. They dismantled the cars themselves. Fink sold a crumbled Renault to my father for $150. After restoration it drove another 90,000 miles. Rosen’s Scrap yard on Port Watson, collected industrial scrap from the mighty metalworking factories around town, loaded it on railroad cars, and sent it back to steel furnaces in Buffalo. Yes, the junk yards were eyesores, but they sure were useful. PS: My father’s large, copper liquor still wound up at Finkelstein’s. Fink was delighted to get it!

CAN INDUSTRY COMEBACK?

Factories boomed in Cortland, NY, for 100 years up to 1990 for these reasons:

Local innovators like Brewer, Brockway, Wickwire, Edlund, Durkee, Smith, Corona, Pall, Thompson, Bement, and others turned their visions into factories.. They stayed in Cortland because the city had the resources to make their businesses successful.

Capital for land, building, and equipment was available from local banks and investors.

Workers were available. They came down off the farms and from overseas with strong work ethic and basic skills.

Transportation was good. Two bustling railroads brought in iron and steel, copper, lumber, flour, coal, and machinery, while taking out trucks, typewriters, wire and cable, machine tools, castings and forgings, boats, and tennis rackets. Roads were good, then excellent after I-81 was built..

The environment suited industry. Heavy snow and rain provided plentiful water for the factory processes. Cold weather made hot work like casting, forging, wire making and running punch presses more bearable in the days before air conditioning. Blowing winds kept the air clear and fresh.

The building codes encouraged factories and houses to be built close. Most workers could walk to work. Snow was not a problem.

– Schools were excellent, and they trained kids to become mechanics, printers, machine operators, repair persons, and clerical staff all to support jobs in the factories.

Making quality goods was a Cortland mindset. Cortland factory standards and workers contributed to making the words Made-In-America mean Built-With-Quality.

Unionization starting in the 1940’s &1950’s facilitated growth. In Cortland and nationally, paying workers more led to growth and prosperity for all. Attaching the label UNION MADE sold more of the product and made you feel proud to own it. Unionized Cortland workers had double the productivity of foreign workers. That’s a fact.

– Taxes on land and equipment were a minor expense after applying depreciation allowances. The tax code actually encouraged investment in equipment as a way of preserving wealth.

Then things changed:

In the 1960’s, most of the factories were sold off to conglomerates headquartered elsewhere. Loyalty between management and employees ebbed away. Little things, like seeing BTC emblazoned on the check stub, had meant something, and now were gone.

-In the 1970’s, worker safety and environmental laws made operating the factories more expensive, but still profitable and viable.

In the 1980’s, changes in technology eliminated jobs. Computers replaced typewriters. Presses replaced hammers. Computerization eliminated office and shop jobs. Robotics replaced some types of workers, though not a lot.

-From 1990 on, jobs moved South and then overseas. Investors chased sharp wage cuts, gave a total disregard to safety and environment, and abandoned quality standards.

After 2000, financialization ended any sense of loyalty or commitment by top management to the communities that had served them so well for decades. Hedge fund billionaires took control, and they had no understanding or appreciation of factory work.

Can it come back?

-The willingness and trainability of Cortland workers to work hard is still there.

-Globalization, financialization, and technology make it difficult but not impossible to bring industry back. European countries have successfully maintained their industrial base by having enlightened industrial policy. We need the same.

Will it come back? In some form, it can and will. Look back to innovation, investment, and technology. Like a century ago, the resources are there and ready to make it happen again.