GETTING STARTED

Factory life was my early destiny. Growing up in an industrial neighborhood in Cortland, NY, I was comforted by the booms and clangs, smells and aromas, smoke and fumes, and sights of factories. They promised prosperity. People in Cortland identified themselves by where they worked. They made boats, trucks, tennis rackets, typewriters, bread, steel wire and forgings. Every dinnertime I heard stories around the dinner table about the hard work of factory life as well as its camaraderie of fellow workers.

When we moved to SC, the communal ethos around work life changed. It was less talked about and I was surrounded anymoe by factories and offices. That left me with little guidance or exposure to the professions or to makling career choices. My work life started in my father’s upholstery shop in a ghetto district. Being there was more a social experiment than a job (see Ardis History). My first paying job was running a peach packing conveyor one summer. Enough money was saved to start college at the U of So Carolina. I was sixteen. The following summer I worked at a bakery back in Cortland, NY. The hours were long, but the pay was much better. Unfortunately, I used the extra money to gamble instead of study, leading to my dropping out of college. That brought me back to the bakery in Cortland as a pastry-line worker. Making cinnamon buns and Danish all night was drudgery. The superintendent kindly told me to go back and get an education. I took his advice at the next job.

The bakery was a large, modern operation employing 250 unionized workers. They shipped out baked goods by the tractor trailer truck loads. Working hours were long and boring. Union membership was mandatory. That gave me insights into labor unions that were useful to my career later. One was that unions were simply the opposing teams in the struggle for resources, not enemies of capitalism. Another lesson was that automation benefits all stakeholders in a business. It makes the company competitive and business grow, while workers get better pay and job security.

Durkees Bakery stories are posted on www.allansposts.net.

BREWER-TITCHENER CORP (BTC)-The forge Shop

My next job was at Brewer-Titchener Corp. (BTC) a forging factory in Cortland. They gave me a trade as a welder. Pay was a step up from the bakery, but the work was dirty, hard, and hazardous. I came home so black with soot that my dog did not recognize me. I got a painful burn and a crushed toe. I needed a different trade. College was unaffordable, so I enrolled in a course to become an electrician.

Union membership at the forge shop was mandatory. But labor relations there were quiescent because the pay was good, and the workers were accustomed to crude working conditions.

Six months into the job, a job posting went up for a technician in the engineering department. An older fellow worker, Rossini C., said to go for it. I got the job. Rossi’s advice perhaps saved my life. As an electrician, I might have electrocuted myself by now.

The technician’s job introduced me to a lifelong friend and mentor, Bill Harrison, the Chief Engineer at BTC.

Bill urged me to get a degree in engineering in night school and persuaded the company to provide tuition assistance. I graduated as an industrial engineer from Syracuse Univ.in 1975.

BTC had two factories in Cortland and 500 employees. Each one had “hammer rooms” with rows of forging hammers. After forging came machining and press forming, tempering furnaces, acid cleaning and galvanizing rooms, Q.C. testing, and shipping. The forging hammer operations were even more arduous, dirty, and hazardous than welding.. Read Eulogy to A Hammerman) for insight in to the brutally tough working conditions of the forge shop.

My work included metallurgical studies, equipment maintenance, plant expansion, and factory improvements to comply with OSHA and EPA regulations came in to effect in the 1970s.Foring work is loud. I became an expert in noise control and even testified in injury claims court.

My next career step-up came when Bill H., the boss, left for a new job just as a major engineering project was underway to modernize the forging plants. I moved in to his office that night I took charge of the project and managed it to a successful completion! The company Gen Mgr., Mr. Ed Telling, quietly approved of my slipping into Bill’s role and his office. I was respected for working long hours and doing a good job completing the project.

A few months later Bill’s position was filled by a metallurginst, Al Sabroff. Al came from a research center and had no experience inside factories. I became his close aide and kept him filled in about how to run engineering department. He appreciated my support and became another of my mentors. He countered some of Bill’s off-base views on factory management, so I got a balanced view from the two.

Telling was trained as an industrial engineer, as I was studying to be. Worker pay throughout the factory was based on time-study, a field of industrial engineering study. Telling made the mistake of replacing traditional stop-watch time-study with a computerized system. The new system was complicated, error prone, slow, and expensive. The workers rejected it. Telling’s entire staff warned him against doing it. It was a failure. Telling lost his job. I aspired to someday be a VP-GM like Telling was, so the lessons from his failure stuck with me. I.e.,if a traditional method works, leave well enough alone. And listen to advice from peers.

I sent Tellng a thank you for sponsoring my college tuition.

Opportunity knocked again when Brockway Truck (now Mack Truck) posted a job opening for an industrial engineer to work on plant expansion. Brockway was only a few blocks away. Leaving BTC was disloyal after all they had done for me, but my sponsors were already gone, so I had little grief.

BROCKWAY-MACK TRUCK

My stay at Brockway Mack was 6 months. In that short time, I learned assembly line techniques, more about time study technique, and more about union-management relations. Mack Truck, based in Allentown, PA, had an adversarial relationship with its union, the UAW. Both sides were tough and constantly clashing. Mack Truck managers came out of the trucking industry and were tough and gruff. They confronted the union directly and ran efficient factories. The labor relations manager said he didn’t care if the union had 400 grievances, “bring’em on”. Learning from him, I said the same thing later at Sprague Electric to the three unions I dealt with.

The Industrial Engineering manager, Wayne D.,. was a smiley rascal that added a lesson in what to do if caught in a tryst. That was part of the ethos of that industry.

The Mack Truck plan to increase the plant output was cancelled. My heart was back at BTC anyway, and they were glad to have me back. They increased my pay and responsibility. The next chief engineer, Constantine “Gus” Anthony gave me free time to complete my college degree. Thank you, Gus.

One last project at BTC was another plant expansion when BTC bought a forging business in Boston and consolidated it in to Cortland. When it finished, my job changed from plant engineering to writing process sheets. It was boring. By good chance. Bill Harrison called to ask me to come join him, I accepted and was soon on my way to Boston, Massachusetts.

The complete Brockway-Mack Truck story is posted as a Labor Day story in www.allansposts.net

ENGELHARD MINERALS AND CHEMICALS CORPORATION (EM&C)

This job change put me in the big leagues. Engelhard Minerals & Chemicals was a Fortune 150 company with operating headquarters in NJ and financial headquarters in New York City. EM&C had factories and offices throughout the world. EM&C’s two divisions were Metals Div and Chemicals Div.

The Engelhard Metals Division was the largest worldwide producer of platinum, silver, and gold. The Plainville, MA, plant where I worked was the largest silver processing plant in the country. It produced silver bullion, gold pens, and silver clad industrial products. The Metals Div’s commodity trading operations in NYC and London set the world price for gold, silver, and platinum each day. The precious metals businesses were always profitable but not steady. Metal profits occasionally had high spikes, as when the Hunt Brothers caused a price bubble and Engelhard took them to the cleaners, and suddenly drops back. During the silver price bubble surge, I knew when the stock price was going to shoot up, but didn’t have money to buy any. Well, at least I avoided committing insider trading. Engelhard had brillant and highly profitable specialized techonology in specialty metals. The automotive catylictic converter was patented by Engelahrd and produced under license to them.

.

Engelhard’s Chemicals Division mined and processed kaolin ore in southern GA. Kaolin is a ceramic material used in paper production. Combining its ceramics and platinum technologies, Engelhard developed the automotive catalytic converter. Profitability of the Auto Catalyst Group was tremendous.

Engelhard’s two divisions clashed in culture. With my roots in both NY and SC, I had a foothold in both camps. The Metals division, operating from the financial district in NYC, dealt with banks, commodity markets, and financial firms throughout the world. Operating plants, like Plainville, kept up with the management pace of its Wall Streeters. The Chemicals division, with its giant open-pit mines in the deep south was less cosmopolitan. The Chemicals Div managers were chemical engineers, all conservatives, who did not trust the precious metal business up in NJ and NYC.. The Chemical people wanted steady, predictable profit, not spikes and lows, and they wanted no hint of the deals that commodities marketers make..

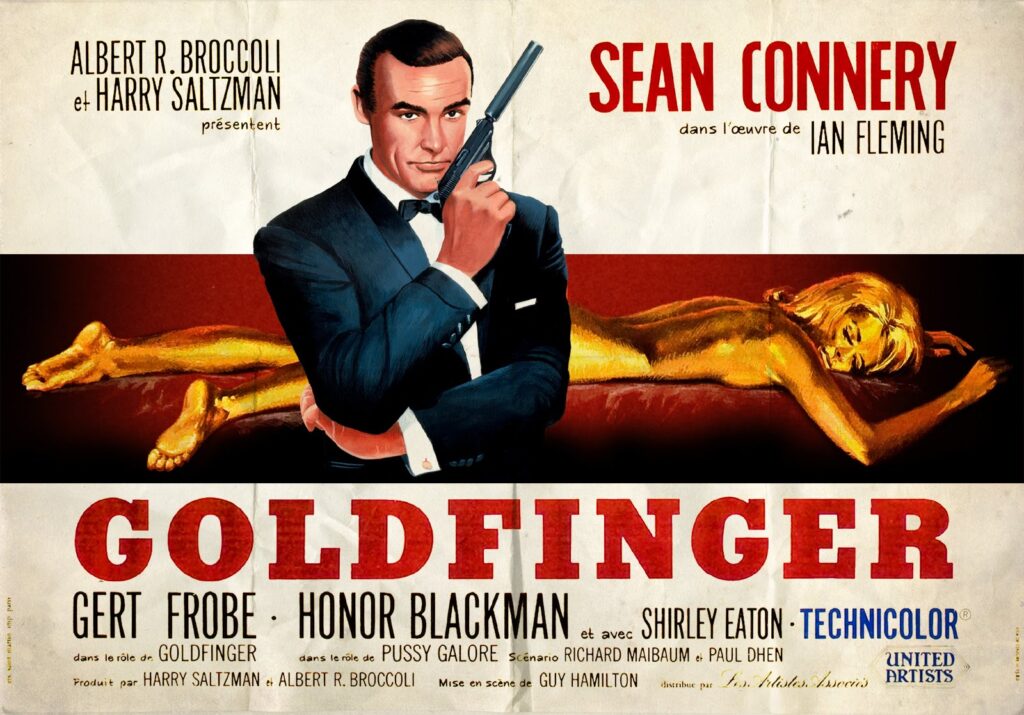

Back in the 1940s, Charles Engelhard, Jr., the chairman, had been a friend of Ian Fleming, the author of James Bond stories. Fleming modeled scenes of James Bond book and movie GOLDFINGER after Charles Engelhard’s exploits with gold transfers after WWII. Engelhard’s death in 1974 still reverberated within the management ranks at the company when I arrived in 1976. His cronies were being shaken out, causing many management changes at the top in rapid succession. This led me to believe that the jobs at the top are always short. I acted accordingly when I got there..

The Metals Division consolidated several plants in NJ into the Plainville, MA, operation. I was hired to consolidate the Attleboro, MA, plant into Plainville and was mandated to avoid cost overruns like had happened on the NJ projects. My two-million-dollar project finished on-time, on-budget. Days at the plant were hectic. I lived close to the plants and came in every evening to work quietly and keep the project under control. My dedication was recognized by management. Credit also goes to my ex-wife as she tolerated my doing so. I gave her one of my bonuses for self-use.

With the project completion, the Plainville plant became the largest and most efficient plant in the country for processing silver.

I was recognized for outstanding engineering and financial control of my projects. Success felt good, but that increased my workload. After two years of working day-and-night all week, I needed to rest up and resuscitate. I was burned out, and my boss Bill did not recognize it.

I sent out a few resumes and left.

MICHELIN TIRE COMPANY

The Michelin Tire Corp. of France was building plants in SC. Michelin’s hiring manager and I both misjudged my reasons for joining them. I thought I would be working on new plant start-up. But that was already done. Michelin wanted me to do small efficiency projects. That was not my forte, and in truth, I just wanted some rest and relaxation. I got it.

Michelin was a fine company, but not for me. They hired top graduate engineers and provided them with excellent training. They expected typical French perfectionism. Unfortunately for Michelin, excellent lunch-time French cuisine could not keep me. Many engineers left. We were over qualified for the work that. Michelin was asking us to perform. For the first time, I dreaded driving to work each morning.

At Michelin, I was just one of many bright young engineers. At Engelhard, I was important. I called back Engelhard. Returning to the company was not uncommon at Engelhard. I got a raise and promotion. They bridged my service time back to my hire date in 1976, which made my record look good and provided some extra vacation time. My career was back on track.

While working in South Carolina, I was able visit family in Sumter on weekends. I had the time to start a fitness program that has kept me healthy for 50 years. My wife became pregnant while there. She had gynecological problems that the local doctors could not deal with. Her doctor back in Boston at Harvard Medical School was glad to see us back. The baby, Matt, was born healthy.

BACK TO ENGELHARD

Back in Engelhard/Plainville, Bill H. was delighted to have me back and piled on major plant engineering projects. First, to engineer a solution to the plant’s environmental control problems. Second, to build a new wing for the front office. Third, to support other engineers with preparing capital appropriation requests, my forte.

Compliance with environmental regulations was a top priority with corporate management. They needed to protect their highly profitable pollution control business from any public criticism. New federal regulations were emerging at that time, and Plainville’s compliance was complicated by its use of several hazardous materials including cadmium and cyanide. The plant’s waste treatment system sort of worked, but at great expense and potential liability. The Plainville operation might be closed if no solution was found. Allan Ardis was assigned the responsibility to find one, and I did so.

I negotiated with the city to extend a sewer line out to the plant, and I justified to the BoD having Engelhard pay for it. Working with a team of civil engineers, we built a showcase system that treated industrial waste and even retrieved some silver that had gone down the drain. The cost was $2,000,000 for Engelhard. The environmental problem was solved. Doing so added 25 more years to all the jobs there. I was a hero.

On a personal note, during the negotiation. I was disputing a large over-charge on my home power bill. The city attorney called the power company on my behalf and the bill disappeared. That was business tit-for-tat. Thank you, Mr.. Attorney.

The office expansion project was also successful. On time, on budget, and handsomely done.

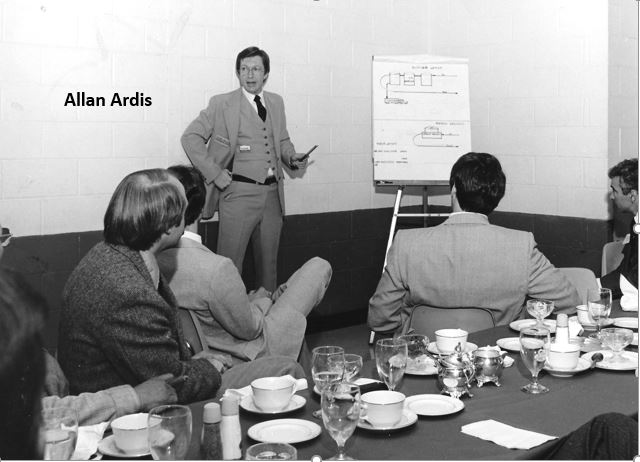

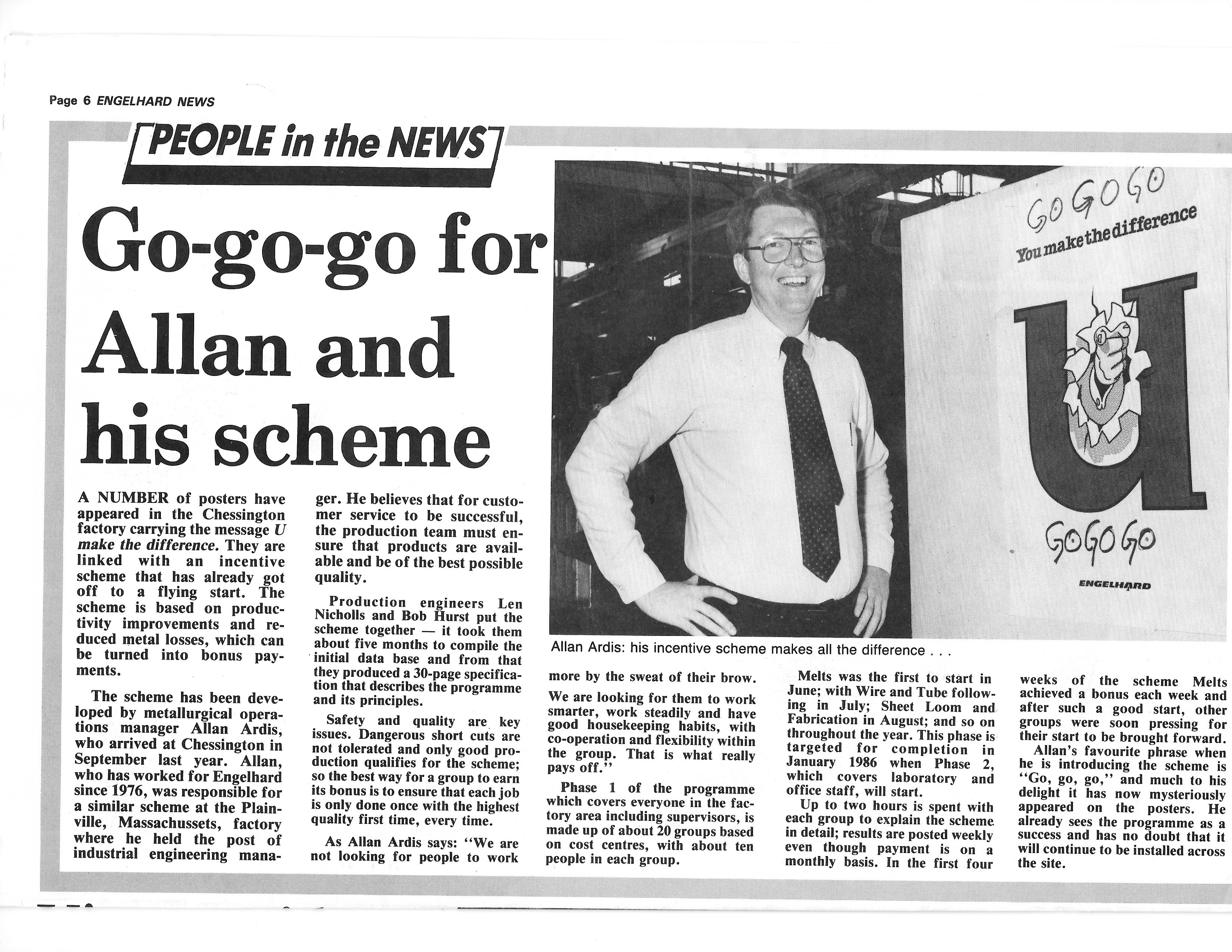

After these successes, Bill was promoted to Director, and I became Industrial Engineering Manager. I had an office, secretary, and staff engineers. As the IE manager, I was responsible for labor work standards, plant equipment modernization, and capital budgeting. I earned the title “the great white hope” for the efficiency improvements of these programs. The capital budgeting work involved preparation of capital appropriation requests (CARs) that kept my name in front of senior people in NJ and NYC. That kept me in the management succession line-up.

Although Bill H. was my great benefactor, his guidance had some downsides. He constantly criticized senior management and antagonized our fellow managers. He referred to Engelhard as the most f_ _ked-up place that he had ever worked. That contrasted with the activity I saw all day in the factory and with the bigger picture of the company. Engelhard plants were modern operations that ran better than most. Plainville hummed along well and profitably. Bill’s negativity clouded my confidence in the company management and affected my career decision making. The top managers dismissed his criticisms as those of a valuable but eccentric engineer. As for the shop floor managers he insulted, I smoothed over the hurt feelings that he caused. Bill was a right-wing political fanatic. I had to ask him to stop telling me every day that the communists were going to take over and turn us into slaves. Lastly, Bill encouraged hard liquor drinking as part of being a manager and becoming an executive. Perhaps it was, but not for me.

Engelhard Corp. sponsored me for the Executive MBA program at Northeastern University in Boston. This program was designed for mid-career executives on the fast track at their companies. Modelled after the Harvard MBA program, the experience was first class and in it I made lifetime friendships. I graduated in 1984 and was immediately transferred to the Engelhard plant in London, England.

Engelhard Corp. had an overseas package for its international executives. The first step was an executive medical exam. I already had signs of having multiple sclerosis, but I did know that, and the exam did not detect it. I was okayed to go!

The transfer for the family went well. My children were small and adaptable, and my wife was pleased to be travelling to Europe. The first three months were exciting, like a trip to Disneyland. Then came the rains and getting used to working with the British. Engelhard managed the household move well. It took me a year to understand and appreciate how well the company was prepared to treat me as an overseas executive. The second year was more enjoyable, but I was ready to come in in mid-1986.

ENGELHARD LTD-

My assignment as European Operations Manager had two goals for the company. It gave me exposure to several of the worldwide operations and to meet executives who could share knowledge of the company back to Charles Engelhard, JR. and his connections to So Africa. This job was my first experience in directly managing factory operations.

The London operation refined gold, fabricated platinum, and managed similar operations in Paris, Switzerland, Rome, and South Africa. Much of the gold refining was for the Bank of England, as bullion had to be re-assayed every time it changed hands. Engelhard fabricated platinum for use in the glass industry. The platinum workers were cheerful, especially when I brought them back cigars from America. Sometimes, though it appeared that they were just going through the motions to keep their jobs in front of this inquiring American, me. The London plant drew platinum into thread and wove it into large sheets used as catalyst in the petroleum industry. One of the platinum wire drawers told me he loved Americans because he was there on D-Day as Nazi slave when we arrived. I set up a platinum coin program. Platinum is difficult to work with because of its high temperature characteristics.

My role in setting the world prices for gold, silver, and platinum was to twice each day reported the factory’s inventory levels of gold and platinum to Engelhard’s London trading desk. This data drove the world prices for these precious metals..

The London plant dealt directly with Russia on platinum sourcing. I declined to travel to Russia because a small blip in world politics might keep me there. I wanted to be home with the family at night in London.

The Brits initially regarded me as a management trainee, but I insisted on having operational responsibilities. I launched a productivity improvement program that was well regarded all the way back to headquarters in the US.

The Engelhard factory in Switzerland resembled the one in the movie GOLDFINGER. But the Swiss were not melting gold.. They fabricated intricate dies used in drawing nylon into filament. Swiss capability precision was applied to food, too. They cleaned beef sufficiently to eat it raw as a spicey hamburger dish that the British loved. No, thanks, I always take my burger well done.

Working overseas was a mixed blessing. I was home sick. Both the weather and working with the Brits seemed dreary. Listening to Sinatra sing “New York, New York” on the way to work did not help. Fortunately, the wife and kids liked it there. I didn’t appreciate all the benefits in the company overseas package, but my wife did. In the second year she got us moved in to very nice house in a posh neighborhood.

Coming back, I was given a choice of assignments to either the plant in Carteret, NJ, or to the plant in Millis, MA. Carteret would have been the better choice career-wise, but choosing Millis allowed me to move back into my own home. That was good for the family. I chose Millis. It was Engelhard’s venture into electronics and looked interesting. I now refer to it as the Millis Curse.

THE MILLIS CURSE

Engelhard Microwave Circuits-Millis was a business nightmare as I walked in, and it got worse. Engelhard had created its Electronics Group as part of the Chemicals Division. The executives in Electronics forecasted a great future for their division then suffered through years of monthly losses while waiting for the business to make a turnaround. It never did.

Three scientists/entrepreneurs created the Millis business and sold it to Engelhard as a “pig in a poke”. It had never made a profit but sounded hi-tech to manufacture miniature circuit boards with gold layering. The execs involved assumed it could be made profitable. But, the facility was dilapidated, the equipment broken or obsolete, the operational staff unqualified, the factory workers unskilled. The VP left in-charge by the entrepreneurs, Tim Davis, a fast-talking Harvard MBA. He had never managed anything more complex than a clothing boutique. When I joined, we both reported to senior vice-president Larry Campbell. Larry was a befuddled chemist and heavy drinker who liked Tim’s nonsensical attempt at management. They got fired together after blustering through two years of failed forecasts. I inherited their poorly conceived plans and got little support for changing them.

I was counted on to fix it all in six months. The HR department sent in a company psychologist, Dr. Frye, to help us. We needed more than that..

Tim and Larry had gotten authorization for $5,000,000 to build and equip a new facility nearby. The plan included replacing all the people. The new facility was built on an old rock quarry with no access to water or telephones. The employees were terminated as psychologically unfit and replaced with more of the same. When the new equipment finally arrived, no one knew how to operate it. Overhead and expense account spending became extravagant. Engelhard’s investment grew to $7,000,000 with no sign of a return on it. I flew down to headquarters every month to present this dismal information. It was humiliating.

It was time to move on. Leaving Engelhard was loss for both the company and me. I had invested 11 years of my life with them. Before I left, a senior manager kindly gave me this advice, “Allan, you didn’t know who your friends were.”

I joined PM Refining in Buffalo, NY.

The final chapter in the “Millis Curse” occurred later when I became VP-GM at Sprague Electric. I hired a sales manager, Frank Smith, a Harvard MBA, who had worked next door to Engelhard-Millis plant while I was there. Frank turned out to be a disaster, too. I wondered if the Millis Curse had followed me.

PM REFINING-

Working at PM Refining was like a year in a TV sit-com..

PM Refining, Inc., was a precious metal refiner and jewelry-maker in a building in downtown Buffalo, NY. The owner, Phil Leonard, was a delightful 65-year-old businessman who operated it like a zany comedy. Phil was in contention with younger men, Paul and Mel, who had helped him start the business and who now ran it. Phil wanted to take control back and hired me to do that. I initially ran a small earring business for Phil and learned some of the jewelry trade. However, Paul and Mel could see what Phil was really doing by bringing me in, and they made the first move. They built a similar business just outside Buffalo, then staged a management walk-out within PM Refining. They took key people and some customers with them. They expected PM Refining to fail.

I gave PM Refining a new life. I took over and kept the operation going through the crisis. Phil’s son-in-law did the same in running Sales side of business.. I reached back to Engelhard and pulled in a set of technologists. This team made PMR more efficient than ever. Led by me, we saved the company. Phil slapped a $500 bonus on my desk. Perry, his son in law, was made president. He was experienced in running the sales side of the jewelry business. I was not to be part of his team, though. Nonetheless, Phil’s whole credited me with saving the business. They allowed me several months as the building manager while I conducted an executive job search. Just in time, I got one. Meanwhile, managing a multi-tenant building in downtown Buffalo was a lot of laughs. It was like being with Dany DeVito in the series Taxi.

PM Refining’s zaniness supplemented my EMBA training. It taught me to be flexible. That helped in the next job.

Living in Buffalo was good. The house was gorgeous. The schools were excellent. Buffalo had culture bestowed in its great days of industrial might. Western New York felt like home. So, the family stayed in Buffalo and worked out of town for the next three years. I commuted home on weekends, catching the New York Central Rail Road in Albany for the 6-hour trip to Buffalo. Other executives were doing the same thing as the heavy industry of twentieth century Buffalo scaled down.

SPRAGUE ELECTRIC COMPANY

The Sprague Electric Company was a great company making electrical components. They helped win WWII with developing the capacitor that set off the A-bomb on Japan. Sprague started winding down in the late 80s. I joined in late 1989 first as Operations Manager, then became Vice-President & General Manager.

Sprague was shaky when I started in late 1989. At Sprague, I made the operations efficient, turned back the clock on the union to give control back to management, and recruited an excellent group of shop managers, technical support, HR, and finance. The company doubled in sales. I saved hundreds of jobs. Details of his story can be found in my post named SAVING BROWN STREET .The Owners recognized my achievements and paid me well. But, after 5 years, my programs for improving productivity were done. I wanted to use this success as a stepping stone to a similar but bigger challenge in some other company. We separated.

I learned at Sprague that the highest compensation went to sales people, so I became one.. As I demonstrated, anyone can be a salesman. Customers want a problem solver, not a golf partner.

I had moved my family and household to Vermont, just across the state line from Sprague’s operation. The house was in the Green Mountains, an hour of hard driving from any airport. It was a remote place from whence to be looking for a new job. So, I followed the conventional wisdom and created my own job.

GUARDPLUS24 SECURITY

I established a security business there in N Adams, MA.

My plan was to use guard services and alarms to generate steady income while I built a business as a manufacturer’s rep for security equipment. Mfg. rep businesses typically operate over a wide territory, use mostly phone sales, and have limited travel. With the right product, I could operate out of this remote location. The local opportunity for guard services was fire-watch services in the old mill buildings left by the Industrial Revolution..

The guard service became a Frankenstein’s monster. It provided a living, but there was more to providing this service than I planned for. Security guards are a mix of police-want-a-bees, unemployed old factory workers, and few serious career guards as gems among the pile. Every ex-con in the county applied and had to be weeded out. It was like managing the cast from John Candy’s movie Armed & Dangerous. They drove me nuts.

My plan for a manufacturer’s rep business had a promising start. I became the national rep for bullet-proof vests made in South Africa. That took me to Washington, DC, to meet with the FBI, the AT&F, and my congressman. I worked a million deal to sell vests to Mexico. But all this preliminary work came to no avail. I did not have the money or the connections to make the ideas work.

The alarm part of my business brought me into electronic security. Starting a business without experience in it was a mistake. I gradually learned the electronics security business from equipment suppliers. But I broke-even or lost money on every sale.

I tried creative solutions to grow the business. I offered the guard services as a franchise. I advertised in the Army-Navy Magazine as a perfect business for a retiring serviceman. None answered. The only buyer was in El Salvador. I told him I could not support a business that far away, but he insisted on being part of an American company. For $5,000, he became one. The profit setting up Guardplus 24 El Salvador was small, but it enhanced my international credentials.

Positive cash flow from the security guard business was not enough. I was stuck in Vermont with a family to support. My luck changed at a security trade show in Manhattan. I met with Securitylink. Its parent was the Bell company Ameritech., a Fortune 100 company. In a few weeks I was working for them and my career was back on track.

I sold the security guard business, keeping enough cash to keep the family afloat until things got better. I relocated SC to try to restart the guard business there. The attempt failed. I went to work for Securitylink.

This was a difficult period of life. Leaving the family in Vermont is painful.

Mt complete story on Sprague is posted as Saving Brown Sreet on www.allansposts.net

SECURITYLINK-FROM-AMERITECH

My Securitylink time was a problem that became an opportunity. I started as a local sales representative. Base pay was so dismal that my wife’s divorce attorney claimed I was under-earning to avoid paying alimony. I was in a remote office and learning on-the-job.

Ameritech as a baby-Bell company went into the security alarm business thinking it was a glorified telephone answering service. It was more than that. Without understanding the business, Ameritech started costing costs. Sales force commissions were cut in half. That caused an uproar among the sales people, including the national account managers. They all quit in droves. The term national account manager (NAM) was new to me. NAM’s handled chain accounts, had a higher base salary, and earned quadruple the commissions of local sales reps like me. I applied for an open NAM job, flew to Texas, and got it. My base pay doubled, and earnings potential made a quantum leap. Side benefits included a private office, an administrative assistant, and an expense account. Securitylink paid for me to move to Atlanta and take over all national accounts in the SE except Florida.

Securitylink’s problem solved my problem.

The turmoil settled down when new senior vice-president, Charlie Platapodis, was hired and restored the compensation plan. Charlie and his new regional sales manager, Gary Green, my immediate superior, became my lifetime friends.

My income stayed in to the six-figures for several years.as I became one of their top salesmen. Store and restaurant chains were growing in the 1990’s, and I had the right skills to work within corporations. Applebee Restaurant chain, where the supply-chain manager said she wanted an engineer, not a salesman, immediately went national with me. I showed respect for women in management whereas my predecessor did not. Next, Target Stores flew down from Minneapolis to insist that Allan Ardis be there national account rep. I solved problems and made sure that their new locations opened on schedule.

A young salesman, Jim B., had filled me in about the national account managers (NAMs) openings which I jumped on. Jim did not apply for a NAM job. He rued that day for not asking for the NAM job himself. I told him later that the lesson was that problems can be opportunities.

Because of my engineering background, Securitylink allowed me sell security system technologies that neither their installation offices nor I fully understood. During the rollicking 1990s, an internet company named iXL flew me to their NYC offices to provide security systems for three floors of a skyscraper. The sale was $500,000 and that zoomed me to the top of the sales roster that month. iXL went out of business before we had to figure out how to make it work, but we got paid for it.

Target Stores had me fly to their headquarters in Minneapolis to inspect their security master system. That put me out on the roof in February in mid-winter Minnesota. Nothing was accomplished om this trip, but it made them feel good that they had an expert like me look at. While there, over lunch, I commiserated with their security manager over divorce alimony we each paid. That chat made for male bonding, and it generated business.

Another case of overselling was WestPoint Stevens, a large textile mill in west Georgia. The security system I sold them was too big and sprawling for Securitylink to do well. The job turned sour shortly after it was started. At one-point Securitylink had thirty trucks of installers out there trying to figure it out. WestPoint’s plant engineers who had selected Securitylink were embarrassed that we were such a bunch of screwups. They quietly used their own electricians to finish the job. The system worked, Securitylink made a profit, no one knew the difference, and I was again regarded as a success. Credit really belongs to nice country folk who trusted that I knew what I was doing and did it for me. They were happy in the end.

My annual review documented that I worked hard. I was first-in and last-out of the office each day and worked Saturday mornings. Sunday mornings I read manuals. Only Saturday and Sunday evenings were for socializing.

My sales grew as I steadily made cold calls. Most salesmen avoid cold calling and wait for business to come to them. My hard-scrabble background gave me the discipline to go find it. Many of the high-rise buildings in downtown Atlanta today still operate with the security systems that I engineered and sold.

I enjoyed working for Securitylink. I heard from the boss only about once per month. My performance was solid, so his time went to those who needed it. I ran my own show.

A special treat for salespersons is going to conventions and national meetings. They took me Pheonix, Las Vegas, Chicago, Miami, Bermuda and other elegant spas. They were fun times.

ADT SECURITY MERGES SECURITYLINK

ADT Secuirty bought Securitylink in 2001, i.e., #1 bought #2.. During a merger, sales people play musical chairs to find their new place in company. I chose Tampa. Because of my prior good work, the company paid to move me there, and I acquired the Outback Steakhouse account.

Outback Steakhouse was a complicated account. Headquarters was in Tampa and Securitylink (now ADT) was their national alarm provider. The difficulty was that ADT often fumbled installations, for instance sending a crew 300 miles to the wrong state and billing for the drive time. I worked long hours to fix all that and make it a success. It was worth the effort. My first year with ADT was the highest-paid year of my career (that backfired on making an alimony adjustment).

I had little respect for ADT. The ADT offices looked professional. Everyone wore suits. I liked that. But in general, ADT managers, technical people, and administrative staff were grossly incompetent. ADT customers were angry all the time with screw-ups. ADT compensated them with money. Billions of dollars flowed in every year for alarm monitoring, and that cash was used to smooth over screwups.

My ADT sales director encouraged heavy drinking and sexual jokes in the office. The abbreviation ADT stood for America’s Drinking Team. Since I was serious and sober, he was not unhappy to see me leave. He was more comfortable with the lunkheads spitting tobacco juice in a can at his meeting and looking up skirts.

Cynthia and I got married in Las Vegas at ADT’s award banquet. We had 400 rooting-tooting sales people at the wedding reception. ADT paid for our mutual travel and the room.

A recruiter had called me for Stanley Security Systems. The position was well-paid, and Stanley was in a premier old-line company. I was ready to leave ADT. Their culture of drinking, carousing, and harassment did not work for me. I accepted Stanley..

I now learned what integrated security systems were. I was already pushing to sell large systems at Securitylink and ADT, where nobody else knew about them either and that almost got me in trouble.

STANLEY SECURITY SYSTEMS

The Stanley Works, known for its tools, went into the electronic security business and organized Stanley Security Systems. They grew through acquisitions, starting with buying premier companies in the industry like Best Locks Corp.. Some of acquisitions that followed made for a bumpy ride for me. I quit was hired there three times by Stanley.

The systems at Stanley Security were complex. Training was comprehensive, from locks to cameras to biometric readers. I spent my first two weeks in Indianapolis learning technical applications from experienced product engineers.

Back home, Stanley converted my garage into an office so I could work from home. That seemed odd at first, but starting each day at home soon became a routine.

My sales territory was Tampa, where there was plenty of business nearby, and all of south Florida for larger projects. Since I liked working on large projects with major clients, I sought out presentations for airports and hospitals across the state. I travelled to Miami and points in between much as I wanted to.

Business got off to a good start. Within two months I booked $600,000. I credit the support technicians and my manager, Vicky D., which allowed sales proposals to close quickly. Although the technicians were helpful, they also began to waste my time just to goof off. I was not patient enough about the wasted time. I called the Sales Manager at a competitor and a week later I was working there. Looking back, the problems at Stanley could have been solved if I had gone more directly to senior managers about the issues. As my boss at Engelhard had said, “I didn’t know show my friends were.

IRCO (Ingersoll-Rand Corp.)

IRCO was another old-line producer of air compressors. The company entered the security system business as manufacturing wound down in this country. They acquired south Florida’s leading security integrator, Security-One.

The acquisition was positive. Security-On brought to IRCO a large customer base, excellent technicians, streamlined software, and a strong work ethic in the office. They worked so hard they made me feel guilty about leaving the office to go home for dinner.

I was lucky to change jobs so easily in my late 50s. However, job changing put me at the bottom of the sales totem pole. I got were dregs, so I hunkered down as before and self -generated business.

My stay with IRCO came only a few months. IRCO’s nationwide strategy was not working. They shut down several offices. Tampa looked to be next, so I looked into an opportunity to work with my former colleagues Securitylink again…

I joined GDI-Global based in Chicago. Until now, I had not wanted to work for a small closely held company. However, now I did. I need another job and some freedom to take care of personal business with my family.

My exit from IRCO was timely. After I left, their staff in Tampa walked out with the customer files and set up a competing company. IRCO security was closed.

electric fence by GDI

GDI GLOBAL

GDI-Global was a one-product company and just a stop-over for me. My friends at Securitylink had formed GDI and had asked me several times to join them. I consistently turned down their offers GDI was too small and too specialized. But when they called again, I joined as an independent sales representative to cover Florida.

GDI’s product was electric fence. It was engineered for safe use near humans. Anyone touching it would be stung but not seriously hurt. The main customers were Exxon-Mobil and prisons.

My first achievement for GDI was meeting up with Chuck Butler, a security system consultant who wrote contract specifications requiring electric fence. I convinced Chuck to specify GDI. Chuck and I became close friends.

The electric fence was not easy to sell. They flubbed the only bid opportunity I created for them.

GDI’s developed one other product, and it was odd, too. It was a lightning detection system. Tampa was the right place for it, being the lightning capital of the country. However, like the electric fence, potential customers were skeptical and reluctant to buy it.

I went back to Stanley, where, as luck would have it, my GDI experience set the stage for my biggest success yet to come.

STANLEY SECURITY -Again

The return to Stanley was smooth. They were glad to see me back. I had always liked Stanley. It had high quality products, well prepared marketing materials, and brand name recognition that made selling and engineering a pleasure. Adding to that, Stanley’s next acquisition of Honeywell Security brought in more of my friends from Securitylink.

Several Securitylink executives had gone over to Honeywell, including Tim Whall, the president. Whall had come up through the ranks and knew me through the national accounts. Now he had become president of Stanley Security Solutions. That bode well for me.

But there was a problem. Honeywell had sold only small systems. My new ex-Honeywell sales manager, Scott M., had never had a project larger than $25,000. To his consternation. I was working on million-dollar ones. We put each other on edge. He could not openly object because Tim Whall was pushing for more of the large sales. Scott tried to sabotage my large sales, but his efforts backfired.

The Pasco Water Treatment Project came together perfectly for me. Marvin K., the water director was from NY, and we became close friends. Chuck Butler, my friend from GDI days, was the consultant on this job and specified electric fence. I bid the security project for $1.5 million. My manager insisted on a high margin, hoping we would be uncompetitive and lose the bid. My proposal was approved by Tim Whall. The electric fence scared other bidders, but Whall trusted all the GDI executives he knew from Securitylink days.

I won the million-plus dollar job! Amazingly, no other security company bid this job.

In recognition of this sale, Stanley flew me to San Antonio, TX, for an award and then with my wife to Palm Springs, CA. My sales put the Florida team over the top in a national sales contest. The entire Florida sales team went. Cynthia and I sat with the president of the company.

Back in Florida, my frustration with my sales manager’s obstacles continued. Despite him, I won a large project at a rural hospital. I felt guilty for overcharging them.

Changing jobs would eliminate my daily frustrations. One call to a competitor did the trick again. and a week later I was working for Johnson Controls. I walked away from the second have of a $40,000 commission on the million-dollar project, but I got an equal signing on bonus.

I wanted to work on large projects, and Johnson Controls hunted the big ones.

JOHNSON CONTROLS INC. (JCI)

The Johnson Controls office had blueprints piled everywhere. The company was run by engineers and installed security systems in major buildings all over the world. I was in the right place.

JCI had one downside. Salesman turnover was high. JCI was heartless in cutting down the sales force during economic downturns.

At JCI, I enjoyed gaining an even deeper understanding of the electronics and software in these systems for giant corporate and government installations.

Chuck Butler, my security consultant friend, came up again. Butler had recently written the specification for an airport security project that JCI had just bid on and lost. JCI sales people involved were clamoring to file a protest with the customer and override Butler’s design. I was pulled into this fray. I reminded them to not alienate a customer and a consultant that you might need again. That input helped my new sales manager, Doug B., to placate sales team.

JCI was impressed with my sales connections. At the U. So. FL, 13th largest campus in the US, a housing director made me a sole-source for their security work. At the Port of Tampa, the security director did the same.

Two special friends at JCI deserve mention. Mark C. was an excellent engineer, Afro-American, and effective sales man. We were a good team with me as a prospector and Mark as a sales closer. I shielded him from racial prejudice I saw in a JCI old-south manager.

The other was Randy C., a fellow salesman. He was likeable enough to get hired age 66 but not smart enough to keep it. He got fired at age 67. Then, I helped him get him his next three jobs. The jobs paid well and were at good companies. I was jealous of the success I was creating for him. Alas, Randy’s only strong suite was getting jobs, not keeping them. But he illustrated that age need not be a barrier.

Back at JCI, changes in the economy pushed my sales production down. Assignment to a performance improvement plan PIP was imminent. The ignominy of a PIP motivated me to leave JCI. My boss, Doug G, asked me not to leave. The 2008 Great Recession was just coming, and I needed a new port before the storm.

I made one call to the sales manager at Siemen’s, the giant German industrials conglomerate. A few days few days later I was working there.

SIEMENS

Siemens was an elegant touch near the end of my career. They provided tastefully appointed offices, high performance computers and software, handsome European-style sales brochures, a company car, a generous expense account, and well-trained technicians. I liked being part of a world-class company again.

Siemens Security was trying to use relationship selling for its security systems and avoid the bidding process. It worked in Europe. This approach requires convincing the customer to simply design and negotiate pricing and skip bidding to others. Siemens’ reputation helped. I sold an entirely new hospital system with sole source pricing. When the Obama administration planned to put a high-speed train between Tampa and Orlando, I almost succeeded in having Siemen’s named for providing the security. But Governor Rick Scott, as much a jerk then as he is now, rejected the money for the plan.

The business travel with Siemen’s included a monthly 5-hour drive to Miami across alligator alley in So Florida to a sales meeting. My colleagues at the meeting were professional and the best I had seen. I was proud to work for Siemens. Helpful. On one trip, Siemens gave me my only visit to Disney World. They owned one of the giant exhibits. It was a giant globe with a moving ride inside. As Siemen’s people, we stepped ahead of the paying customers to board. I was at the right place.

I had one success with a large hospital system, but overall, “relationship selling” selling was not working. I changed jobs again, and this time I helped my sales manager leave, too. We both went to Stanley.

STANLEY SECURITY III–The third time was a charm

I was welcomed back to Stanley for the third time. The office had a new manager, Lee Hough. Unlike his predecessor, Lee H., wanted his office to sell million-dollar systems. I was that right salesman for that. The million-dollar water treatment project I had sold was completed and Lee had gotten credit for closing out the project profitably. We became close friends, my only annoyance being that he listened to Rush Limbaugh every afternoon.

Stanley had me fly to Minneapolis for more training again. This time, I did more teaching than learning.

Back on the job in Tampa, I was in good shape. Stanley’s IT dept. had computerized the proposal preparation process and made my job easier and enjoyable. Lee H. was out to win big jobs and set competitive margin requirements. I was given had a lot of latitude to set my own selling agenda and strategy. I brought back previous customers.

The new sales manager insisted that I follow the sales routines designed for junior sales people.. I complied, and squirmed a bit, but the discipline was beneficial. It made me a better salesman, broadened my contacts, and made each day more interesting.

Stanley made still another acquisition that brought in a new partner for me, Joe F. He was a retired cop from Boston. He needed my help to learn about the Tampa market. We teamed up and rode like two-cops on a police force beat. I shared my contacts and network, found opportunities for us, and engineered the job estimates. Joe was effective at closing these deals. Like a cop handling a suspect, he muscled project managers into signing orders. We were the best sales team in the office. Then I was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. My ability to walk quickly declined. Joe said, “No one cares if you use a cane.” Nevertheless, I was 63, and it was downhill from there.

I went on disability and retired nine months later. Stanley treated me respectfully as I left.

Lee H. retired, too and was replaced was my former sales manager from Siemens, Jorges Ferandez. Both Joe F and Jorges F thanked me for my help.

CONCLUSION

My work saved businesses and hundreds of jobs. My career ended with pleasant experiences. I enjoyed working, but my wife reminds me that no one wants their tombstone to say,” I wish I had put in more time at the office”.

My final wish is that it says, “Allan helped many others”.

Allan C. Ardis

RELATED POSTS in www.allansposts.net

- EULOGY TO A HAMMERMAN

- DURKEE’S BAKERY, A HIDDEN TREASURE

- SECURITYLINK-PROBLEMS ARE OPPORTUNITIES

- SPRAGUE-SAVING BROWN STREET